Part 2

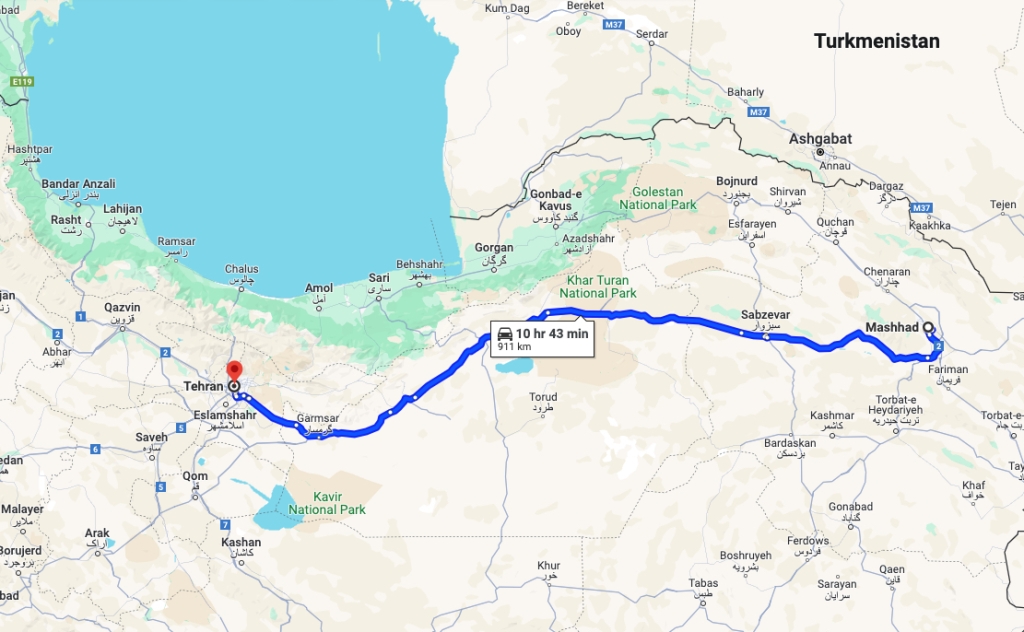

Bus travel is always interesting. You sit in a vehicle with a community of strangers and yet you are separated from them, in your own seat, next to the window or next to the aisle, sometimes with someone sitting beside you, sometimes alone. I liked sitting alone. But on the journey from Mashhad to Tehran the bus was full. Not packed. Full. And not everyone was going to the capital. People got on and off in between.

Iran was very different from Afghanistan. People dressed differently. The men dressed like Greek men did, grey trousers, white shirts mostly with the sleeves rolled up a little because these were working men traveling to take something somewhere, on business of some kind, or to visit family. Women were on the bus as well. One or two wore a head covering, a white cotton extension of their clothing that was thrown casually across the head, covering only the back part of the dark hair that flowed underneath. These were obviously not professional women, office workers or women with jobs that would require clothing that was approaching fashionable. But none of them wore black robes and none of them were veiled and neither the men nor the women displayed any kind of religious fervor.

Some of the same near-hippies I had seen on the bus into Mashhad were also on this bus. Young, dressed in the loose shirts and pants they had bought in India in order to mirror the Indian style of dress, guys with longer hair, not Jesus locks, without beards — beards hadn’t become fashionable yet — who sat more or less together in small groups. Some of them knew each other. Some of them just stuck together for the comfort of being with people who looked like them, talked like them, thought like them, and were just as anxious to get back to tell their stories, show off their trinkets, and slowly melt back into life in their own country, their own city, their own family.

Not me. The purpose of my journey was not to go back to anything. I was going to London, to meet my half-brother David. I had vaguely heard of him once or twice from my mother, but nothing specific had ever been revealed. Until his letter arrived. It was addressed to me, but my mother had opened it and read it. I didn’t know anything about the letter until she decided to show it to me. A rectangular envelope, white, with my name written in blue ink over the address of the Italian Embassy in New Delhi, a bunch of multicolored stamps, some with the stars and stripes on them, stuck not very neatly in the top right-hand corner, cancelled by two black circles which indicated that both the US postal service and the Indian postal service had OKed their veracity and their correct value for the journey the envelope and its content had taken by air from the USA.

Its content.

Its content changed the way I perceived the world. As I read the letter, I stood with my back to the broad window and the glass door which led out to the balcony. My mother stood at the opposite end of the room against the white wall. She watched me carefully. When I read the sentence that broke through the fog of lies my mother had enveloped me in for almost 25 years, I looked up and saw her watching me for a reaction. A cold shower of goosebumps spilled over me from the top of my scalp, down behind my ears, down my neck, over my shoulders and all the way down my legs until the tingling reached my feet. I had been asleep for so many years. I was awake now. I was in a new life. Disoriented. The woman watching me was my mother. I didn’t know her. I couldn’t identify her as my mother. She was a woman watching me for a reaction. She was aware of what had just happened. She was waiting to see how the situation would develop. She said nothing. She just stood there, vigilant.

I read the letter through to the end. David wanted to meet me. We were, according to him, brothers. Half-brothers. I corrected his words as I read them. What I couldn’t correct was his age, the date of birth he had written in the line that had cracked open my world. He was three-and-a-half years older than me. Older.

I looked up at my mother again after I finished the letter. She had the beginning of a smile on her lips. The kind of smile you imagine a fox has after you find out that what you believed was your pet red bushy-tailed dog was actually a sly chicken-stealing predator. I looked at the letter again and realized it had arrived at least one week before she let me see it. She said: “He called. He is flying to London.”

And I was on my way to meet him.

Bus travel is great because every once in a while there is a bathroom break and you get to walk around outside in the fresh air – in Iran of course it’s heated air on the road from Mashhad. But slowly we were climbing and the air was getting cooler with each stop. The longer stretches were for sleeping. Then after the bathroom breaks and tea breaks and a walk, I’d be refreshed and could carry on reading until I got drowsy.

Sometimes the seat next to me was empty, sometimes a man would get on the bus and sit next to me after a polite greeting and a polite smile and him packing his carrying bag or bundle wrapped in cloth in the overhead luggage rack. There was never any attempt at conversation. My various seat companions were as uninterested in conversation as I was, and that made the journey pleasant for us.

Being an only child is a privilege. All the attention was on me. All the love was mine. No competition from any siblings made for peace and quiet but, because my mother was such an extrovert, one of those people who suck the air out of a room when they enter it, I became an introvert. Being an introvert is also a privilege. I can sit alone in a room or in a crowd and be happy thinking my own thoughts. Introversion enabled me to become a creative person, to dream up stories, to observe the world without being distracted by a screaming younger brother or sister, and not being dominated by a brother or sister who was born before me.

The lie I had been told was that my mother and father divorced soon after I was born and he went back to the USA to continue his career in the army and then remarried and had more children. He was a captain (that part was true) and he had been stationed in Trieste after the war. Trieste was occupied by the British, the Americans and the French. The fourth occupying force, the one that had the harbor and the southern coastal area along the Adriatic was Yugoslavia. In that aspect, at that time, Trieste was like Berlin. But instead of the Soviets, it was Tito’s Yugoslavia that made up the last quarter of the international occupying force.

My mother’s lie held until David’s letter arrived. And though I had been bathed in the shower of cold reality and truth after reading it, I was not at all anxious about my relationship with my mother. David was not her child. I was. Yes, she lied. It was part of her professional competences to be able to lie convincingly. She was in the diplomatic service. That’s what they do every day. They lie convincingly so that the foreign nation they are dealing with will engage positively with them. Of course the nation they are dealing with lies as well. Both know that the other is lying. Both accept the rules of the game and get along anyway. It was only me, naive, trusting, who believed everything my mother told me and never once doubted it.

That naiveté and firm trust in my mother’s lies helped me get through grade school and high school unscathed. Had other children at anytime sensed that I was lying or covering some dark secret, my life would have been filled with insults that burn more than fire and brimstone. Being a True Believer (in my mother’s lies) made me invulnerable. The long bus journey to Tehran, plus being an introvert, made the situation absolutely clear to me. Later, when I found out about where she had been and what she had gone through during the second world war, I understood that her mastery of the skill of the perfect lie had been the reason she survived. And she used that mastery to help me survive as well.

Eventually, the bus reached the outskirts of Tehran. The bare landscape gave way to rows of buildings along the side of the road, then to taller buildings, then to traffic that crowded the bus from in front, from behind, and from each side. We were back in what people like to call civilization.

The chaos of civilization becomes apparent once you get off the bus – this time at a real bus station where lots of other busses were parked. Noise. That is the defining characteristic of civilization. The chaos of disorderly noise. Nearby, people were talking loudly in order to be heard, all around me the sounds of cars fighting traffic, horns blaring, scooters racing by, motorcycles breaking wind in rapid bursts, this being the permanent hum of life at an ear-shocking loudness that would not decrease in volume even during the dark hours of the night in this, the metropolis, the capital city of a civilization more than 10 times older than the one now dominant across the Atlantic.

Because I was Travellin’ Light I had no problem with luggage. But I was also traveling fast, and so I wasn’t looking to stay in the city for very long. My priority was to find a bus that would take me onto the next leg of my journey, to Tabriz and then from there to Erzurum in Turkey. From Erzurum there was a train that could take me to Istanbul, and from Istanbul I would be able to hop on the legendary Orient Express to London.

I asked the bus drivers – as usual always more than 3 in order to get the right answer – and eventually found out that there was a small office not far away where I could buy a ticket for a bus to Tabriz. That rather dark and cluttered office was run by a very friendly man in a white shirt that had obviously been worn all day and was therefore well-wrinkled, sleeves rolled up to show forearms with an abundance of black hair, his face with the obligatory black mustache, a head of black hair, slightly curly, greying at the sides like the stubble on his chin. He told me that the bus would only leave in the morning, early, at six.

Luckily for me, he spoke good English, and intuitively understanding my condition, he said: “I close the office in 2 hours. Come back. You can sleep over there.” He pointed to a rather ordered array of bulky green canvas sacks that looked like they could be bags of letters. But they had no printed indication that they were part of an official postal service. “Clothing. Made here in a factory. For the shops in Tabriz.” He followed the answer to my unasked question with a smile. “I will wake you in the morning.”

I had the ticket in my pocket and left my rucksack on the bags that would be my bed that night and walked out into the chaotic evening that was descending on the energetic and totally nonthreatening big city. I trusted the man in the office, I trusted the myriad faces around me – most all of them men – and I trusted the delicious street food I found not far away. I was careful to remember landmarks so I could find my way back to the ticket office. The writing on signs was illegible to me. Arabic numbers were not a problem because those I had learned to decipher, as I had a few of the letters of the alphabet, but words were another thing altogether.

Iranians speak a Persian language called Farsi. Farsi is an Indo-European language related to English through an ancient history that you can look up for yourself if you like. But Islam conquered the country and eventually (over about a century or two) more or less erased the native religion of Iran, Zoroastrianism, and the Arabic alphabet became the standard. Still, because the Iranians have a history that outdates Islam by a couple of millennia at least, there are cultural remnants of Zoroastrianism, the most obvious and most popular being Nowruz, the Persian New Year celebration that takes place at the Equinox, usually between the 19th and 21st of March each year.

Well-fed and happy that I was able to find my way back to the ticket office, I settled onto my bed of bags for the night, with my faithful green blanket to cover me, while outside the locked office the noise of life continued unabated.

Sometime before six, the office door was unlocked, the friendly ticket man came in, made Turkish coffee on a hotplate, gave me a cup of the brew and then led me out and around the corner to the bus that was going to take me to Tabriz. I shook his hand and he patted me on the back, gave me another friendly smile and I stepped through the door into the bus.